He has been labeled a “serial startup producer” but says focusing on spin-offs is bad. He’s soft-spoken, but he’s also a tough critic. And what some might call promising fields of research, he avoids as bubbles. In our interview, Prof. Philippe Renaud from EPFL gives a glimpse of his independent thinking.

Director Microsystems Laboratory 4

Philippe Renaud is Professor at the EPFL in Lausanne. He is Director of the Microsystems Laboratory 4 at EPFL, Member of the Swiss Innovation Council, of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroingeneering and of the Advisory Board of the Swisscanto Growth Fund. He has co-founded the NanoBiotech Montreux conference and is Scientific Advisor to the Startups Aleva Neurotherapeutics and Biocartis.

Microsystems Lab 4 at EPFL, which you direct, is a renowned startup factory: Biocartis, Sensimed, Mimotec, Aleva, and Lemoptix (which was bought by Intel) came from there. What is your secret?

The truth is that I never wanted to create startups with the Lab. What we have been doing for over 25 years is technology-related research. We strive for radical innovation. Often it is not clear at all where our research will lead to, and this is how it should be. We can’t and won’t predict what works and focus on such conjectures because we would exhaust our ideas pretty quickly.

But the director of a lab certainly influences the mindset of the people working there and can encourage them to become entrepreneurs.

It isn’t my job to push somebody. All the founders came to me. In such a case, I’m happy to act as an advisor and mentor. But it’s not just on me, as there are quite a few alumni of the Lab that became entrepreneurs, they all talk with each other and act as motivators. But my most important task is to prepare the researchers working in the Lab for real life. As I tell them, their chances to end up sitting in my armchair are slim, so they must learn to look for opportunities and things that might work. But I don’t want to compromise the scientific quality of the Lab. We’re driven by problems, not solutions. Many times people from the industry want to visit our Lab, but I always tell them they’re going to be disappointed because they’re just going to see stuff that doesn’t work. The few things that eventually work don’t stay in our lab.

Wouldn’t it be desirable that professors would act as business angels as well since they’re at the heart of innovation? A startup that is backed by a professor certainly has a reputational advantage.

You know, two decades ago founding a company was exceptional. Now everybody seems to dream of building the next big startup. That’s not a good development. Professors shouldn’t be too actively implicated in startups, because this may impoverish their future research, it will direct it to a certain goal and inevitably leave less room for other ideas. Us professors should prepare future generations, they are our long-term investment. That being said, I have been implied in startups in rare cases and with limited involvement. I sometimes have the feeling that the pressure to create spin-offs from universities is too direct.

How can there be pressure to create spin-offs?

Counting spin-offs has become a metric. It affects a university’s rankings, and our institution has to fight for its place in these rankings like everybody else. And like other short-sighted metrics, it pushes people to do things they’re not particularly good at. It’s the same question as the necessity for professors to publish as many articles as possible at all cost. I don’t want to come across as an old conservative, I do embrace change. But two decades ago there still were professors who might not have had a fundamental academic vision but were extraordinary teachers or mentors. Today, there is extraordinary pressure to align your profile with what everybody else is doing.

“Today, there is extraordinary pressure to align your profile with what everybody else is doing.”

It’s not just the university’s task to create startups, societal conditions must be conducive to entrepreneurship as well. And in this regard, Switzerland has certainly developed in the right direction.

There can never be too many startups, I agree. People need to be ambitious and should get political encouragement to start their own business. But while everybody has their eyes set on fast-growing startups that receive external financing, budding entrepreneurs shouldn’t forget that one can build a very profitable business with self-financing too.

How can political support for startups be improved?

We have a tendency to like shiny new buildings we can inaugurate, innovation parks and the like. I think startups could do with a more modest environment if they got useful help like legal and financial advice for free. What has certainly gotten better are the many startup prizes that are out there that provide some cash and feedback to the startups. A few years ago I would have said they’re not worth it. The problem with all prizes and “top” startup lists is that the jury has to look at the companies with the eyes of an investor. Otherwise, it’s just insignificant if some journal declares that these are the formidable startups. I could also mention in passing that Verve Ventures has become better and more professional. In the beginning, I wasn’t a fan of the model and found the startups you selected rather arbitrary.

You sit on the advisory committee of the Swisscanto Growth fund together with Steffen Wagner, one of our co-founders. How did you connect to Swisscanto?

This happened through an introduction of my personal network, I didn’t know them before. Their people came to my office with some files and I told them that I don’t understand all these business numbers. Although they didn’t say anything, I could see in their eyes that they were quite worried (laughs). Now I can say I bring a complementary vision to their decision process, and I really enjoy working with them.

Let’s come back to your work as a scientist. What is Microsystems Lab 4 working on?

The foundation of our work is microtechnology, which means the ultra-miniaturization technologies based microelectronics-device processes. One obvious application of microsensors is for smartphones, but there are many others. At the moment, we work on two main questions, the first being: What can we do by applying electrical measurement methods at micro-scale to tissues or single cells? One application that has already begotten a spinoff is deep brain stimulation. The direct electrical connections of cells with microelectrodes may open new perspectives in electrophysiology and biosensing. A second question we work on is: What is possible with microfluidics? These are, in essence, just very tiny pipes, so small they can even let single cells pass.

“This is how our economic system works, it has a propensity to produce bubbles, not just in finance.”

Organs-on-a-chip and even organisms-on-a-chip are an interesting field and draw attention now. Are you working on such things as well?

It is a kind of fashionable topic, not yet fully developed, but with interesting perspectives. We did some preliminary work at the time but didn’t follow that avenue because I have the feeling there is a need to go back into basic biological questions and on physiological relevance of such systems. There is some risk of hype on this topic. This is how our economic system works, it has a propensity to produce bubbles, not just in finance. Don’t get me wrong, it’s important to do research and to publish about topics that are hot at the moment, especially if you still have to establish your new labs.

If you have that kind of freedom, EPFL must be a good place to work.

In Switzerland, we have a stable financing base for fundamental research, unlike in the US, where every institute must run after financing. We’re lucky that we don’t have to follow trends. But make no mistake: If one is completely alone in a field for their entire life, it’s probably not worth studying.

Written by

WITH US, YOU CANCO-INVEST IN DEEP TECH STARTUPS

Verve's investor network

With annual investments of EUR 60-70 mio, we belong to the top 10% most active startup investors in Europe. We therefore get you into competitive financing rounds alongside other world-class venture capital funds.

We empower you to build your individual portfolio.

More News

11.03.2021

We’re now called Verve Ventures

Europe’s leading digital startup investment platform formerly known as investiere is called Verve Ventures. Verve Ventures has become one of the most active venture capital firms in Europe.

16.09.2019

“Startups in Switzerland have great potential”

EPFL is not only one of the best universities in the world, but also a place where promising high-tech startups are created. Verve Ventures has backed a lot of them. We visited Prof. Martin Vetterli, the president of EPFL, in Lausanne and talked about science, technology, and entrepreneurship.

29.07.2019

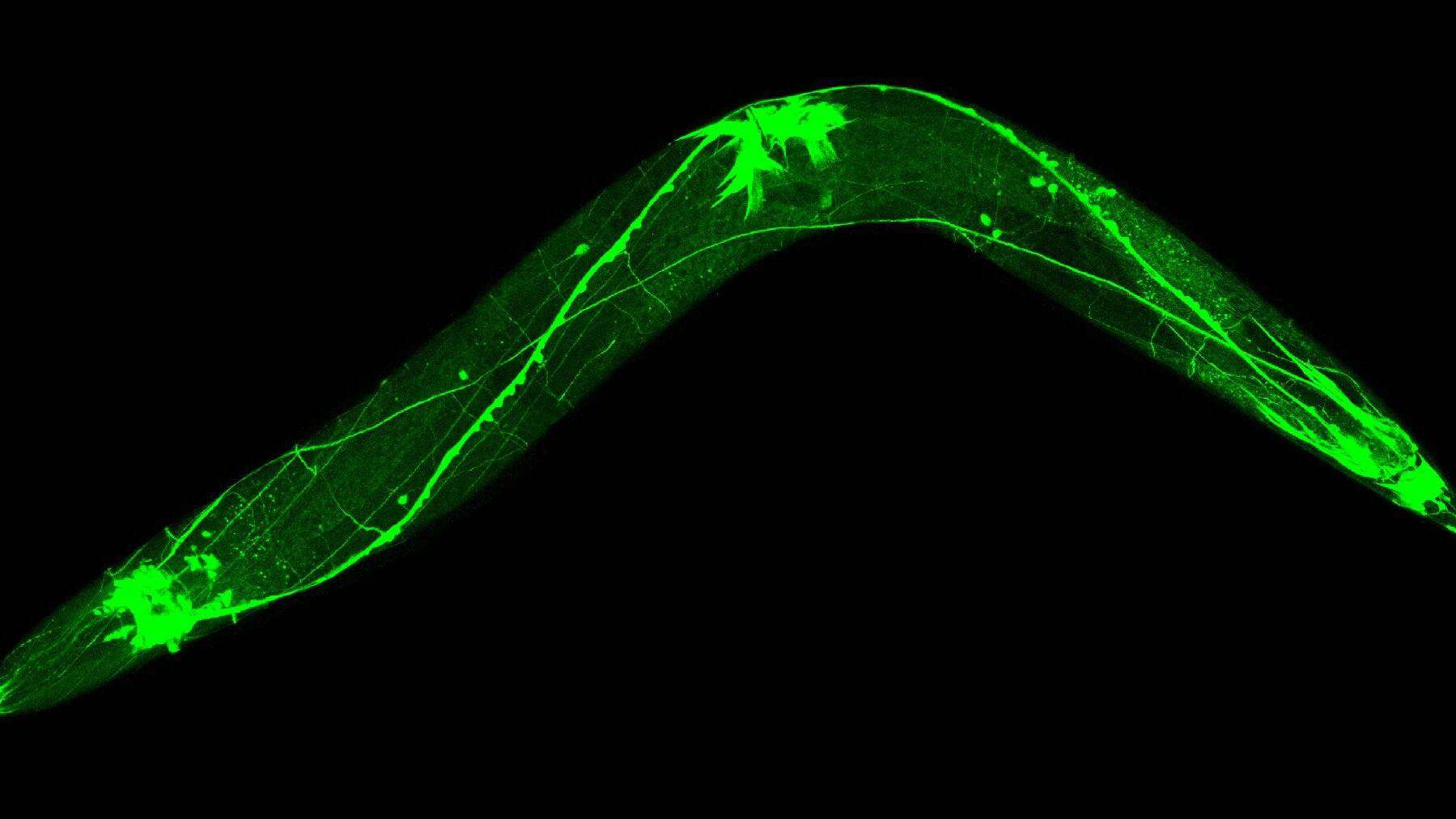

“The worm is very close to humans”

In this interview, Prof. Johan Auwerx from EPFL tells us how to eat if we want to live longer, what small worms can teach us about Alzheimer and Parkinson, and how the startup Nagi Bioscience removes bottlenecks in scientific research.

Startups,Innovation andVenture Capital

Sign up to receive our weekly newsletter and learn about investing in technologies that are changing the world.