Family companies and startups should work more closely together, says Professor Nadine Kammerlander. But she also warns about the difficulties that arise if expectations aren’t managed properly. The next generation of family business owners faces the herculean task of future-proofing their companies.

WHU

Nadine Kammerlander is an economist and leads the institute of family business and Mittelstand at WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management. She focuses on innovation, employees and governance in family businesses and family offices. She was an assistant professor at the University of St. Gallen and holds a degree in physics from TU Munich and a doctorate in business administration from Otto-Friedrich University Bamberg. She worked as a consultant for McKinsey & Company and advised international companies in the automotive and semiconductor industries. Her research has been published in international journals and received renowned prizes. She is co-editor of “Family Business Review” and a member of several editorial review boards.

You wrote your dissertation about family businesses and disruptive technologies. How did you come up with this topic?

In his book “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, Harvard professor Clayton Christensen describes the challenges of listed companies when facing disruptive technologies. While it captures the topic with aplomb, I thought that this topic merits being covered through a different lens, one that I was always interested in, the viewpoint of family companies. I was and still am convinced that innovative transformation is the biggest threat to family firms.

A threat? When talking about family firms, we usually hear about their strengths. Why would innovation be a threat to them?

They do have a lot of strengths that set them apart and lead them to success. They are independent, long-term oriented, and can take quick decisions without bureaucratic hurdles. The lack of outside pressure allows them to pursue new opportunities despite initial setbacks. Think of a retailer that took the first steps towards e-commerce years ago and initially flopped, but due to the tenacity of the owners eventually found the right approach. But today we’re living in a new world where no industry is safe from disruption. This is dangerous because family firms often have one weakness in common: an older patriarch who is the sole decision-maker and has a very narrow network of like-minded people around him. These firms frequently lack advisory boards and the internal diversity that would allow them to identify new trends. Furthermore, family firms tend to be risk-averse and shy away from big investments in new unproven technologies. They tend to use their established team and processes to get better at what they do – this is incremental innovation. But for disruptive innovation, they need to develop new ways.

But family firms are by default innovative, otherwise, they wouldn’t still be around.

In 2016, in a metastudy, we analyzed quantitative data from all over the world and found that family firms invest less in innovation than other companies, but that their projects have a higher success rate. In other words, they’re doing more with less. But we also see a digital divide opening up. On a broader scale, family firms that cannot make the transition to the digital world will either shut down because they won’t find a successor or be taken over. On the other hand, we see family firms that explore new ways of transforming themselves. “Maschinenraum” is a good example, it’s an innovation ecosystem that gathers German SMEs and family firms and explores topics of the future.

Generally speaking, what are the different ways that family firms could leverage innovation for their business?

A study about the German “Mittelstand” [small and medium-sized enterprises] identified three main aspects of this. The first term is “historic capital”, which refers to the position of the firms in the past and the values that follow that help them communicate their purpose and drive change. In this view, the next generation of digital natives from the family that grew up knowing the company by heart plays a pivotal role in reimagining its purpose. Provided, of course, that the patriarchs are ready to devolve power to them. I recently had an exchange with a company lead by a 98-year-old that still had a tight grip on a family firm and wasn’t ready to let go…

The second term is “collaborative capital” and describes the way these firms have traditionally always worked with a handful of suppliers and customers to improve their offerings. A central tenet is that a firm’s employees are responsible for improvements and not just figurines filling a prescribed role.

The third and most recent term is “family venture capital”. More and more family firms are starting to explore ways to invest in startups or outright buy them as a way to tap into innovation. This takes a change of mind, as family firms are usually aiming to pay high and stable dividends to their shareholders instead of doing such investments.

Let’s take a closer look at the last point. While family venture capital sounds like a promising concept, it is also a highly specialized field that requires a particular skill set that family companies might not possess. What are the challenges?

Experienced leaders of family firms usually have a very good gut feeling about good opportunities for their companies because they’ve been leading the operations for decades. The problem is that their gut feeling will fail them when it comes to investing in startups, which as you mentioned, is a different skill set. I’ve heard from startups that say family firms as investors are very cute. They don’t ask critical questions and their due diligence is superficial. This shows that family companies have a knowledge deficit and need professional support in this field.

They would surely profit from working with a company like Verve Ventures which has more than a decade of experience in venture capital and a broad portfolio. We could offer access to investments and also establish partnerships with startups. However, there is a certain reluctance to take the first step from family firms.

I hear that the interest in working with startups is high, certainly much higher than a decade ago, but there are also plenty of examples of failed common projects, which tend to discourage the family firms so they’re reluctant to try again.

Invest in Startups

As one of Europe’s most active venture capital investors, we grant qualified private investors access to top-tier European startups. With investments starting at EUR/CHF 10’000, you can build your own tailored portfolio over time and diversify across stages and sectors.

This is a bit like the story of an otherwise sophisticated investor who told me he once invested in a startup that eventually failed, and therefore will never do that again. Diversification is key. But what are the issues that cause the collaborations you mentioned to fail?

First of all, insufficient expectation management. One of the biggest problems I see is that the understanding of communication and speed differs largely from startups to family firms. Keeping one’s word is a central value of many successful family companies. If they say they’ll deliver by the end of March, they will usually already deliver a few days before that, and the quality will be flawless. Family firms systematically underpromise and overdeliver. Startups, on the other hand, often promise a lot to get into a collaboration and then underdeliver because of resource constraints. They provide a 70% result that is 2 months late. For you as an investor, this isn’t surprising. You know that a startup won’t meet its ambitious goals, and you disregard the information in its business plans. But family firms struggle to accept such an outcome that goes against one of their central tenets. Such issues need to be addressed very early on.

Let’s circle back to the topic of family firms’ willingness to innovate. The next generation of family members, younger and more digitally savvy, could be an important driver of change. But how big is their impact in reality?

Ideally, the older and younger generations reach a consensus about what needs to be kept intact and what could be changed. This again starts with a discussion about values. The tradition of delivering the best quality to customers, for example, might be deemed unalterable, but the way how it is delivered might be up for debate. There also needs to be a clear understanding of who is ultimately responsible for deciding about changes. The problem starts when the management team, which is often quite similar to the patriarch, isn’t open to change. This can lead to an uncomfortable situation where the junior who takes over the reins has to change the management team despite the unspoken rule that nobody gets fired in the family firm.

Does innovation need to hurt?

It certainly leads to discussions about a company’s culture. You shouldn’t forget that many people don’t automatically think digitalization is a good thing. When they hear it, they fear losing their job, and they will find countless ways to sabotage every effort in this direction in their daily work. The company’s leadership needs to clearly communicate that the goal of digitalization isn’t to save personnel costs but to position the company for the future. Digitalization, by the way, starts with processes, then products and services and finally reaches business models. But often even the most basic steps of working towards a paperless process fails because of internal resistance.

Do you see a difference in terms of eagerness to embrace digitalization across industries?

It depends a lot on the power of the customers and suppliers and how much pressure they exert. If there are but a few and big customers that say we won’t continue working with you unless you adopt electronic logistic processes, change can and does happen very rapidly. With B2C-focused companies, there is less pressure. But in general, most companies manage to somehow adapt to new realities. I see a bigger threat in these companies missing the big changes in innovation that are bound to happen by, say, not harnessing the wealth of data they collect. Our rigid understanding of data protection in Europe is a very big barrier that doesn’t exist in other parts of the world. I fear that this might come to haunt us in the future.

It might also come to haunt the citizens of states where data is easily used to subjugate them… but let’s end this interview on a more positive note. Sometimes, the next generation might also want to drive change by establishing a new venture instead of having to reshape an existing organization. How is it possible to leave room for this motivation while assuring that it somehow still benefits the family firm?

There are examples of that. Simon Vestner founded Digital Spine to build a digital infrastructure for smart buildings. The family company Vestner, which builds lifts, was established in 1930. If such an initiative is to succeed it makes sense for the startup to be really independent of the family firm. It doesn’t make sense to just rebaptize one department of the company and expect it to produce radical innovations. This means that the startup needs its own employees, is open to outside investors, and most probably will be situated in a major city, not in the middle of nowhere like the family firm, because otherwise, it can’t attract the necessary talent. But despite this independence, regular exchanges between the companies can be established. In the end, this is but one specific way to explore the topic of innovation and transformation. The necessity to do so should be the top priority of family firms. And increasingly, it is.

Written by

WITH US, YOU CANCO-INVEST IN DEEP TECH STARTUPS

Verve's investor network

With annual investments of EUR 60-70 mio, we belong to the top 10% most active startup investors in Europe. We therefore get you into competitive financing rounds alongside other world-class venture capital funds.

We empower you to build your individual portfolio.

More News

27.09.2022

“A guest lecture on entrepreneurship is not enough”

WHU - Otto Beisheim School of Management is one of Germany’s most prestigious business schools and produces more unicorns than most European universities. This year, Verve Ventures has already invested in two startups founded by WHU alumni, namely marta and Erste Hausverwaltung (EHV). Time to find out what makes WHU an ideal training ground for future entrepreneurs and speak to Maximilian Eckel, who heads WHU’s Entrepreneurship Center.

11.02.2021

“With startups, you invest in a memorable experience”

Entrepreneur, investor, and mother of three, Vvivi Hu has been part of Verve Ventures’ community for a long time. In this interview, she talks about how a venture capitalist mindset helped her become a better investor.

19.08.2019

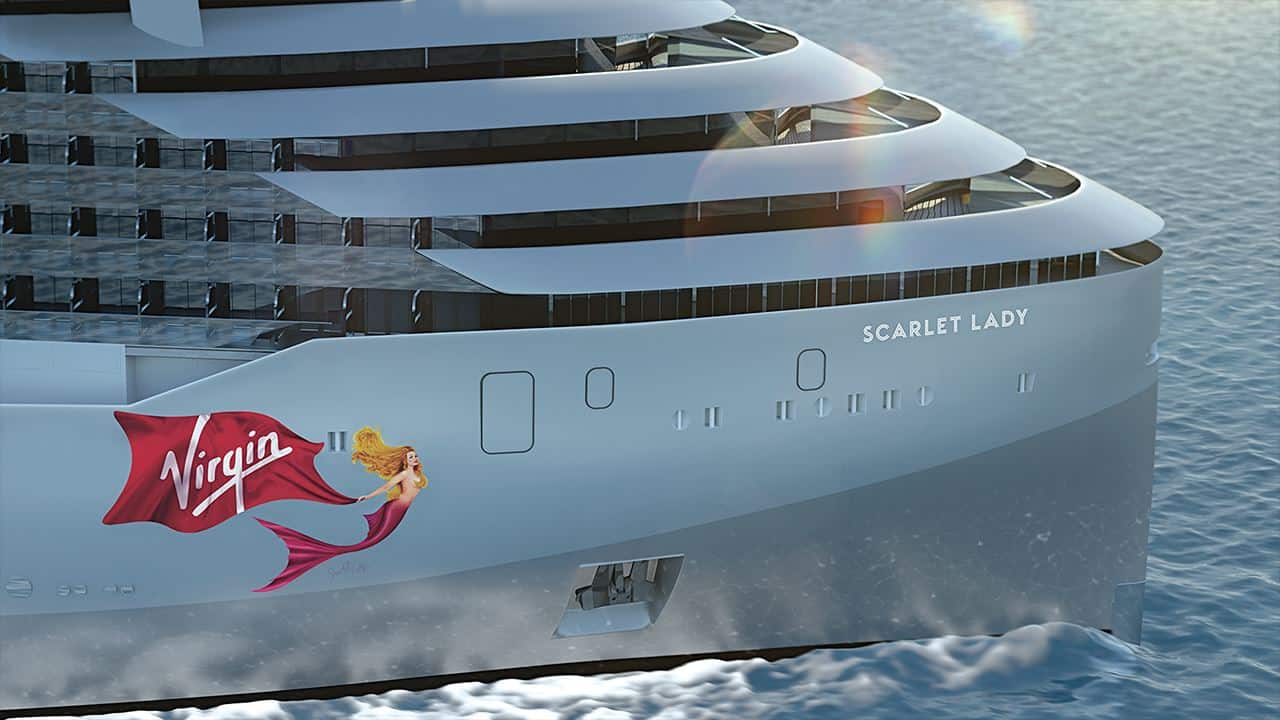

Why companies and families need a mission

Gabriel Baldinucci is a successful entrepreneur and was Vice President on the New Ventures team at Richard Branson’s Virgin Group. He’s now developing new projects for Singularity University in Santa Clara, California. In this interview, Gabriel talks about the importance of innovation for corporations and wealthy families.

Startups,Innovation andVenture Capital

Sign up to receive our weekly newsletter and learn about investing in technologies that are changing the world.