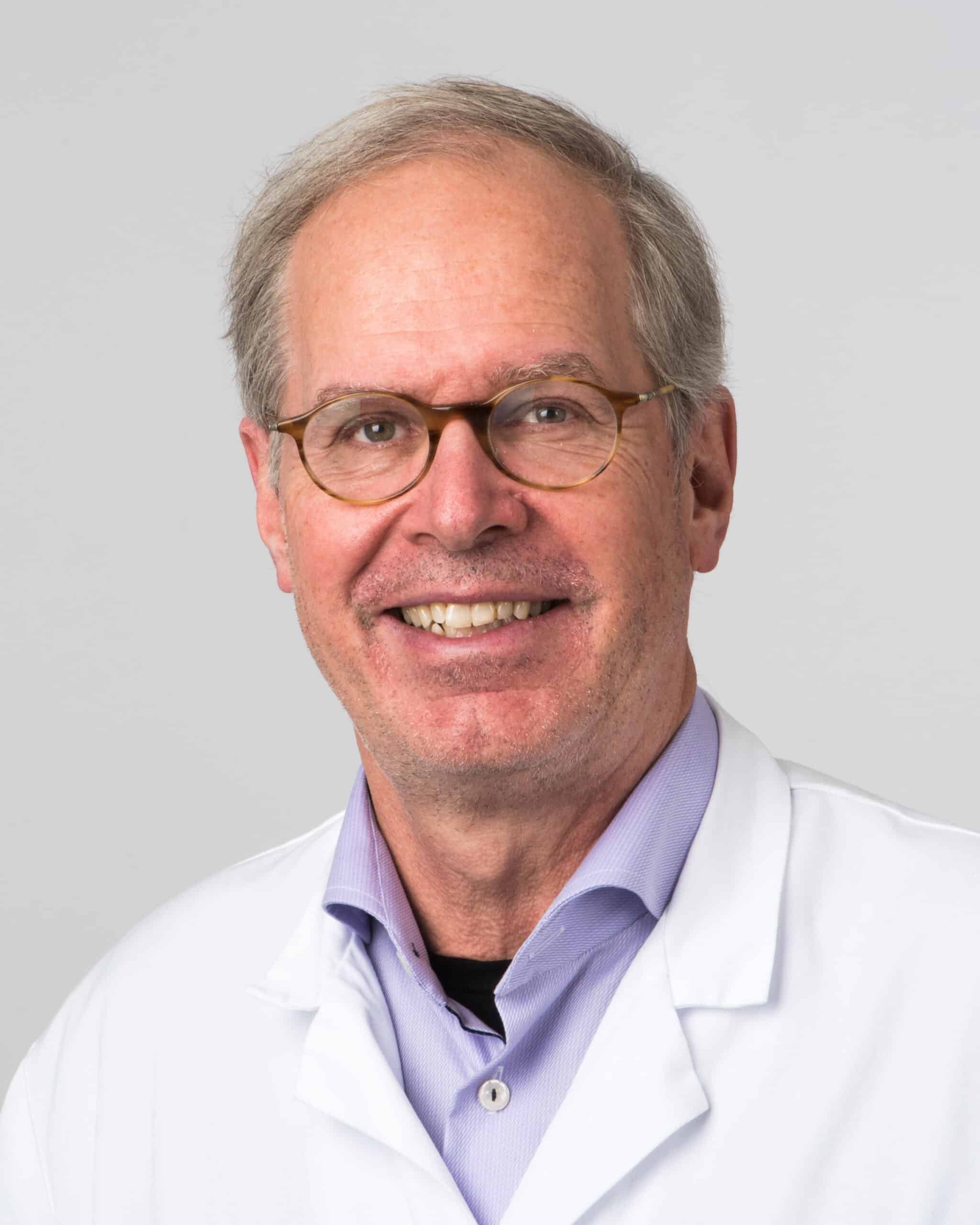

In this interview, the renowned cardiac surgeon Thierry Carrel explains what happens when the heart becomes weak, what the different treatment options are and why the new approach from the startup Fineheart sounds promising.

Professor of Surgery

Thierry Carrel is a Professor of Surgery at the University Hospital of Zurich. He is author of more than 780 peer-reviewed publications, co-editor of several international journals and member of two dozen professional associations. Thierry has received numerous awards, including the Da Vinci award of the EACTS as best teacher of Europe. He has led more than 12’000 interventions (as surgeon, teacher or assistant) and operated on a Swiss Federal Council. A book and a documentary film about Thierry’s work have made him a public figure. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Next to all your professional occupations, you still find time to go on humanitarian missions. Why do you do that?

I’m convinced that if you have the privilege to work in a well-organized health care system, you should be able to give something back to society in general, worldwide. And teaching teams of surgeons in other countries how to operate well even with modest means is not only useful, but also a fascinating challenge. I’ve also seen heart diseases that are almost nonexistent here, like adults who survived their childhood despite congenital heart diseases.

Let’s turn to a topic that is very prevalent in western countries with aging populations and unhealthy lifestyles, namely severe heart failure. Can you explain what this is in layperson’s terms?

The mechanical stress on the heart muscle leads to a fatigued muscle over time. Several diseases contribute to it, but the result is the same: the heart loses some of its pump capacity. Heart failure is common in older people, but can also appear in much younger people. Covid-19 has led to inflammations of the heart in few people as young as 15.

What can you do when the heart doesn’t pump as much blood as it should?

Depending on what the cause is, medications can help the heart to regain its strength in the large majority of patients, but modern cardiology is increasingly confronted with very severe cases where the only cure is to support the pump function with a mechanical device. Some of these patients may recover but if the heart failure is severe, only a heart transplant can give hope.

“Modern cardiology is increasingly confronted with very severe cases where the only cure is to support the pump function with a mechanical device.”

You have publicly fought for several decades to increase awareness and the number of heart donors. How successful was this effort?

Although the transplantation of organs is well accepted, I am a bit disappointed that information campaigns haven’t changed much the opinion about organ donation and that the population is still quite reluctant to make this “final gift” for someone in need. But I am against measures that coerce people to donate if they don’t opt out, I think this should be an free individual decision without the involvement of the state. And we shouldn’t forget that even if there would be more donor organs available, some patients wouldn’t receive one because they’re too old, too frail for the operation, or have rare blood types which mean a long waiting time. On the other side, a heart transplantation is only a good palliation, because the “life expectancy” of the donor heart is always limited and the recipient is dependent on life-long strong medication.

What are the alternatives?

There are different mechanical circulatory systems to support the failing heart, either until recovery (which is quite a rare outcome) or as a bridging strategy until transplantation. In recent years, even a so-called destination strategy has been accepted as a final treatment for some of these patients. These devices help the heart to pump sufficient amount of blood. Years ago, the patient obviously couldn’t move and was tied to a heavy machinery. However, miniaturization has made the system portable but the problem here is that the batteries are outside of the body, and that there is at least one cable coming out of the body that has to be connected to the power source. Such pumps give the patients some quality of life, but need a lot of instruction.

How do you implant such a device?

We still need to open the chest so far and support the circulation with an extra heart-lung machine during the operation. The majority of systems are introduced through the apex of the left main chamber. All in all, the operation lasts maybe 2 to 3 hours, depending on the patient’s condition. If it’s a patient’s first heart operation, it isn’t too complicated, but it can get quite challenging if they already have had bypass or other heart surgeries. The good news is that since the 1990ies, when the first generation of these devices appeared, everything has become smaller and more user-friendly. But it is still a medium-sized intervention, comparable to the implantation of a heart valve. The problem with these devices is that they create abnormal blood flows and that the patients need to take blood thinners in an extremely disciplined way. If they take too much, they risk spontaneous bleeding, if they don’t take enough, they risk blood clots.

How big is the risk of the surgery itself?

Here, the timing is quite essential. You shouldn’t do it too early of course, but you also shouldn’t wait until the heart failure is so pronounced that the patients have water in their lungs and other organ disfunction like kidney or liver failure. In an optimal setting, 30-day mortality should be around 3-5%, but in severe cases it can be much higher (20%). This might sound like a lot, but for the patient and the relatives, it’s still better than no alternative.

You’ve looked at the novel heart pump the startup Fineheart is developing. What is your assessment?

There are two things that are radically different and therefore extremely interesting from the current alternatives. First, the power source is inside the body and can be charged wirelessly, which eliminates the need for cables and the risk of infections associated with them. Second, the small turbine accelerates the blood flow in a natural way through the heart valve. It doesn’t need, like it is the standard today, a new way that goes out of the heart chamber and pumps the blood from outside back again to the aorta. This, together with the synchronization of the device to the natural pulse, seems like a very good improvement to me, and I am quite interested to see this new technology in action.

Written by

WITH US, YOU CANCO-INVEST IN DEEP TECH STARTUPS

Verve's investor network

With annual investments of EUR 60-70 mio, we belong to the top 10% most active startup investors in Europe. We therefore get you into competitive financing rounds alongside other world-class venture capital funds.

We empower you to build your individual portfolio.

More News

23.03.2021

Professor Courtine and Superman’s Legacy

In 2014 Grégoire Courtine founded the startup Onward to improve the lives of people bound to a wheelchair. The impact of this technology based on neurostimulation seems unreal, almost magical, but will be felt soon.

11.03.2021

How RetinAI negotiated a multi-year partnership with Novartis

Alexandra Ragalie from our portfolio success team talks to Carlos Ciller, co-founder of RetinAI, about the challenges the startup faced when it entered a cooperation with Novartis.

16.01.2020

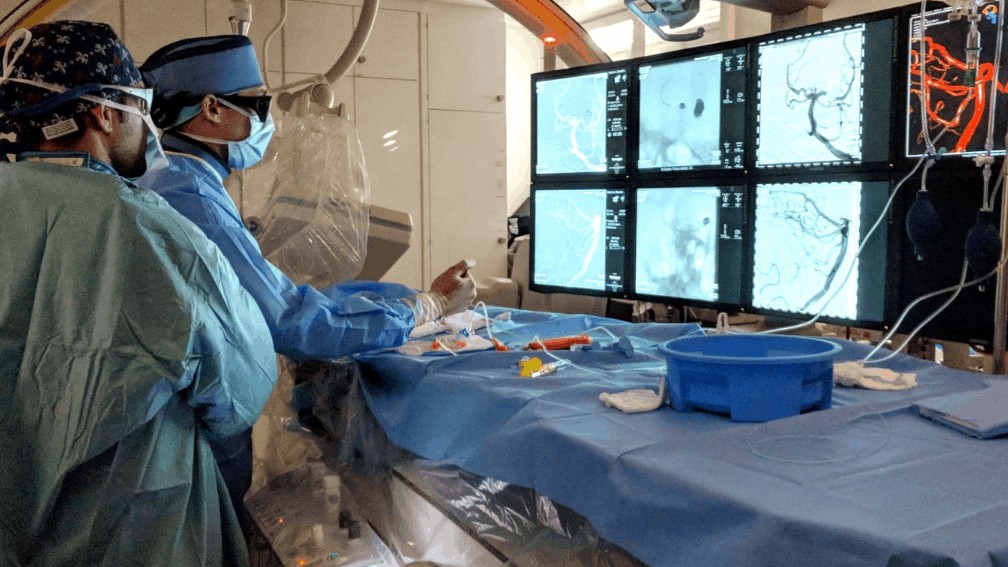

“I’m a brain plumber”

Stroke is a serious medical condition that affects the brain of 15 million people each year. Since the 1990s, continuous technological improvement enables more lives to be saved year after year. Interventional neuroradiologists can perform operations in a minimally invasive way, guided by modern imaging technology. In this interview, endovascular neurosurgeon Pascal Mosimann explains how.

Startups,Innovation andVenture Capital

Sign up to receive our weekly newsletter and learn about investing in technologies that are changing the world.