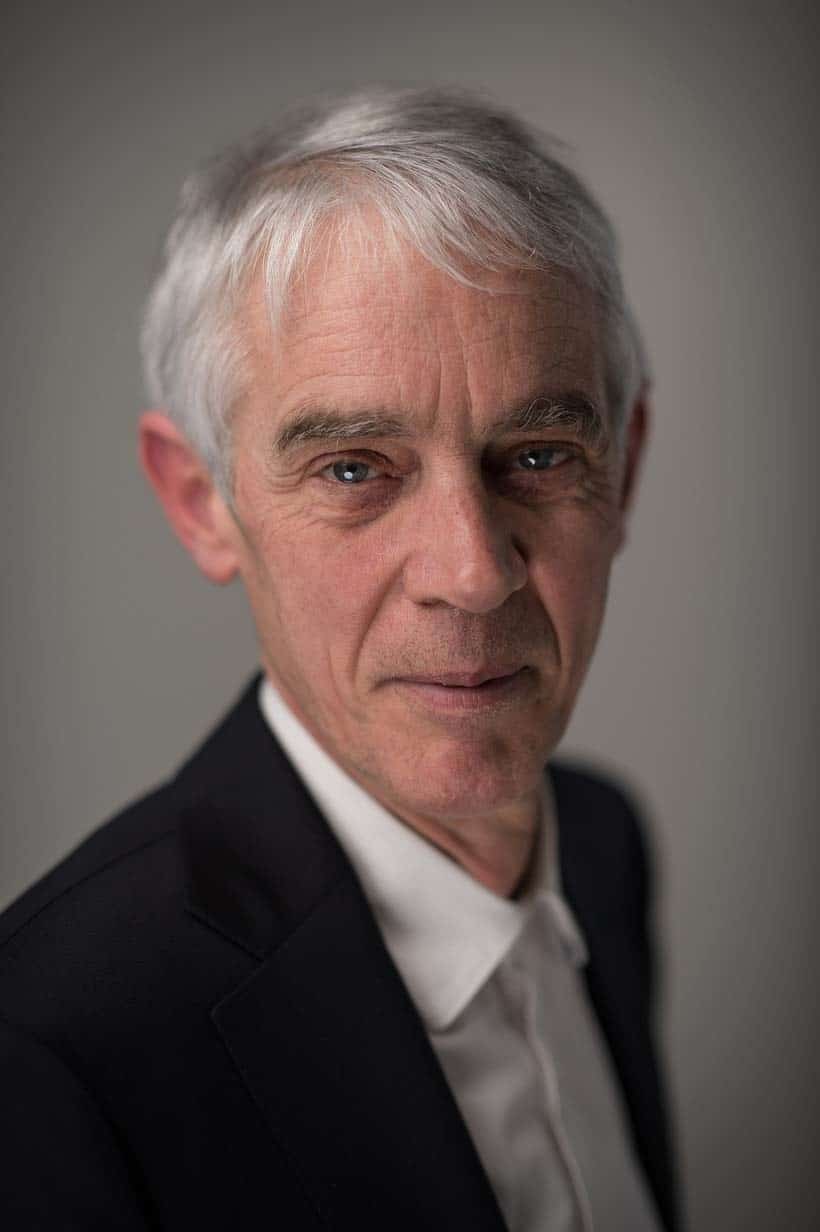

EPFL is not only one of the best universities in the world, but also a place where promising high-tech startups are created. Verve Ventures has already backed a lot of them. We visited Prof. Martin Vetterli, the president of EPFL, in Lausanne and talked about science, technology and entrepreneurship.

EPFL President

Prof. Martin Vetterli is the president of EPFL in Lausanne, one of the world’s leading technical universities with a budget of almost CHF 1 billion Swiss Francs and over 5000 staff. Half of the 10’000 students are of foreign origin.

Martin has been president since 2017. He was president of the Swiss National Science Foundation from 2013 to 2016. He has taught Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Columbia University before becoming a full professor at EPFL, and he has also taught at ETH Zürich and Stanford. Martin is co-author of about 50 patents, some of which laid the foundations for startups including Dartfish and Illusonic.

People seem to ignore scientific evidence: they leave their children unvaccinated, shy away from genetically modified food and ignore climate change. Why is science in the 21st century confronted with so much opposition?

I think that your assessment is wrong. The Economist magazine recently published a study showing that more people trust scientists today than a few years ago. This is good news. So there isn’t a general mistrust towards science today.

Is it a duty of scientists to explain their findings more clearly to the public?

Yes, it is the responsibility of scientists to explain what they are doing. But it is also a delicate task. We shouldn’t over-communicate and create false expectations. Imagine what damage it could create if, say, a laboratory that works on a cure for cancer explains its findings in a way that leads to disappointment later. Scientific reality is complicated. Our communication must take that into account.

Science being complicated doesn’t absolve scientists of their duty to interpret their results, or does it?

Science is agnostic to interpretation. The role of the scientist is to provide knowledge and results. The interpretation of these findings has to be done together with society. And society will also decide how to use scientific progress. Take localization as an example. Advancements in this field can be used to guide autonomous vehicles or missiles. But the decision on how to use science is a task for our broader society.

Coming back to the point of credibility, what is the most important thing that can be done to improve the public’s faith in science?

I am a staunch advocate of the Open Science movement. It calls for transparency on the basis of research. Scientific tradition is grounded in publishing a summary of the results in prestigious journals. But the data and algorithms on which the findings are based usually aren’t made transparent. This makes it difficult if not impossible to recreate and verify the results. The Open Science movement wants to change this.

This sounds like a nice concept. Why isn’t it the standard operating procedure yet?

It takes much more work to make all the data available than to just publish the findings. The Open Science movement began in certain domains like astrophysics and ideas usually take time to propagate. The good thing about Open Science is that it makes results verifiable and if there is a problem, it is going to be detected quite rapidly.

What can you do to foster the Open Science movement?

First and foremost, it is communication. When I worked for the Swiss National Science Foundation, I pushed for all publications that were funded by public money to be open to the public. But in general, scientific work is a matter of habit and also of the pressure to publish rapidly. This will take time to change. But I’m quite confident that the proportion of non-reproducible science will diminish in the future. And it must, because we have examples of how wrong things can go. In the domain of neuroscience, it has been proven that statistical methods in a widely used analytical software were inaccurate and that there could be thousands of scientific papers affected by this.

One thing is the ability to reproduce scientific results, the other is the willingness. Who will spend money on redoing something that already has been done?

It is a widespread concern that nobody will make that effort. But I recently had a conversation with the head of research of a pharma company. He told me that as a principle, the company doesn’t take any scientific paper as the truth. They reproduce every finding that is relevant to them. So I think that science will be challenged.

Let’s talk about science and entrepreneurship. How can you provide a more supportive environment for entrepreneurial professors?

EPFL has three main tasks: education, research, and innovation. We have an innovation team that acts as an interface between research and industry. And amongst professors, you’ll always have a spectrum of different characters. For example, the microsystems laboratory of Professor Philippe Renaud has spun off more than a dozen companies, while the work of Professor Maryna Viazovska, who works on mathematical sphere packaging problems, will probably not give rise to dozens of spin-offs, even if her work does have practical applications. But the most important element is that professors have an entrepreneurial mindset. If they don’t, spin-offs aren’t going to happen.

Is there pressure on EPFL labs to create spin-offs?

No, but there is pressure to be relevant. That’s an important distinction. EPFL has a mission that is different from the non-technical Swiss universities. We have to be in very close contact with the economic reality, be it in the form of collaboration with big industrial firms or by other forms of exchange, like the creation of startups. EPFL’s contribution to society is that we help to keep and improve the living standard in Switzerland. And the most important way we do this is by educating people that will enable Swiss companies to be at the forefront of innovation.

How actively should Professors promote entrepreneurship?

First of all, we already do this on an institutional level. We recently introduced the so-called “EPFL XGrants” that support students who want to start a company. And we also have the Innogrant program for doctoral students. We thus clearly foster a culture of entrepreneurship. Furthermore, students and postgraduates are close to other founders on the campus. The professors themselves can use one day of their week for consulting and helping startups. This can be very valuable, up to a certain point.

Do license payments for intellectual property created by EPFL bring in significant amounts of money?

If we had something like the Google patents I would certainly know (laughs). Patents aren’t a big money-making business for us and in any case, they’re unpredictable. However, license payments should represent a fair return on what the public has invested into basic science.

You criticized the Swiss venture capital scene of not being “vibrant” enough. Why?

Because in Switzerland the number of important and internationally well-connected venture capitalists is still too small. Due to this, startups still hit boundaries in their growth relatively quickly.

Can you give a concrete example?

Take Pix4D, a drone software company that was spun out of EPFL. They had an incredibly attractive offering which allowed them to grow to around 100 employees quite quickly. Then the company was sold to Paris-based Parrot. In hindsight, that was too early. If more growth capital would have been available here, it might have grown to a much larger size before being sold. There are other examples of companies that didn’t realize their full potential because finding 1 million Swiss Francs is possible, but finding 20 million Swiss Francs or more is still very difficult. However, the growth funds that have been established recently are a good development.

What else needs to be done?

People need to realize that startups in Switzerland have great potential. I can say with confidence that engineers that come out of EPFL have a better education than those in Silicon Valley. What is still lacking is a critical mass of serial entrepreneurs, business developers, and talented marketers. Startups need more than just engineers. That’s why we also nurture our relationship with business schools like IMD and HEC. When I was in New York a long time ago, the majority of the business students dreamt of a Wall Street career. Now they want to go to San Francisco. I think the same cultural change is happening in Europe.

Should Switzerland become more like Silicon Valley?

No, we need to find our own model. But you should always try to learn from the best. Take Israel, for example, that has found a way to grow its startups in an impressive way. Silicon Valley might be great for technology, but culturally it is a desert, like the rest of the US. In Switzerland, we can have high tech, culture and beautiful nature in one place. This combination is hard to beat.

Written by

WITH US, YOU CANCO-INVEST IN DEEP TECH STARTUPS

Verve's investor network

With annual investments of EUR 60-70 mio, we belong to the top 10% most active startup investors in Europe. We therefore get you into competitive financing rounds alongside other world-class venture capital funds.

We empower you to build your individual portfolio.

More News

12.11.2020

The big data myth

Data is more than abundant. But instead of creating value out of this “new oil”, companies struggle to work with the data they already have. In order to change that, a completely new approach is needed, explain Prof. Anastasia Ailamaki and Lars Färnström from RAW Labs in this interview.

29.07.2019

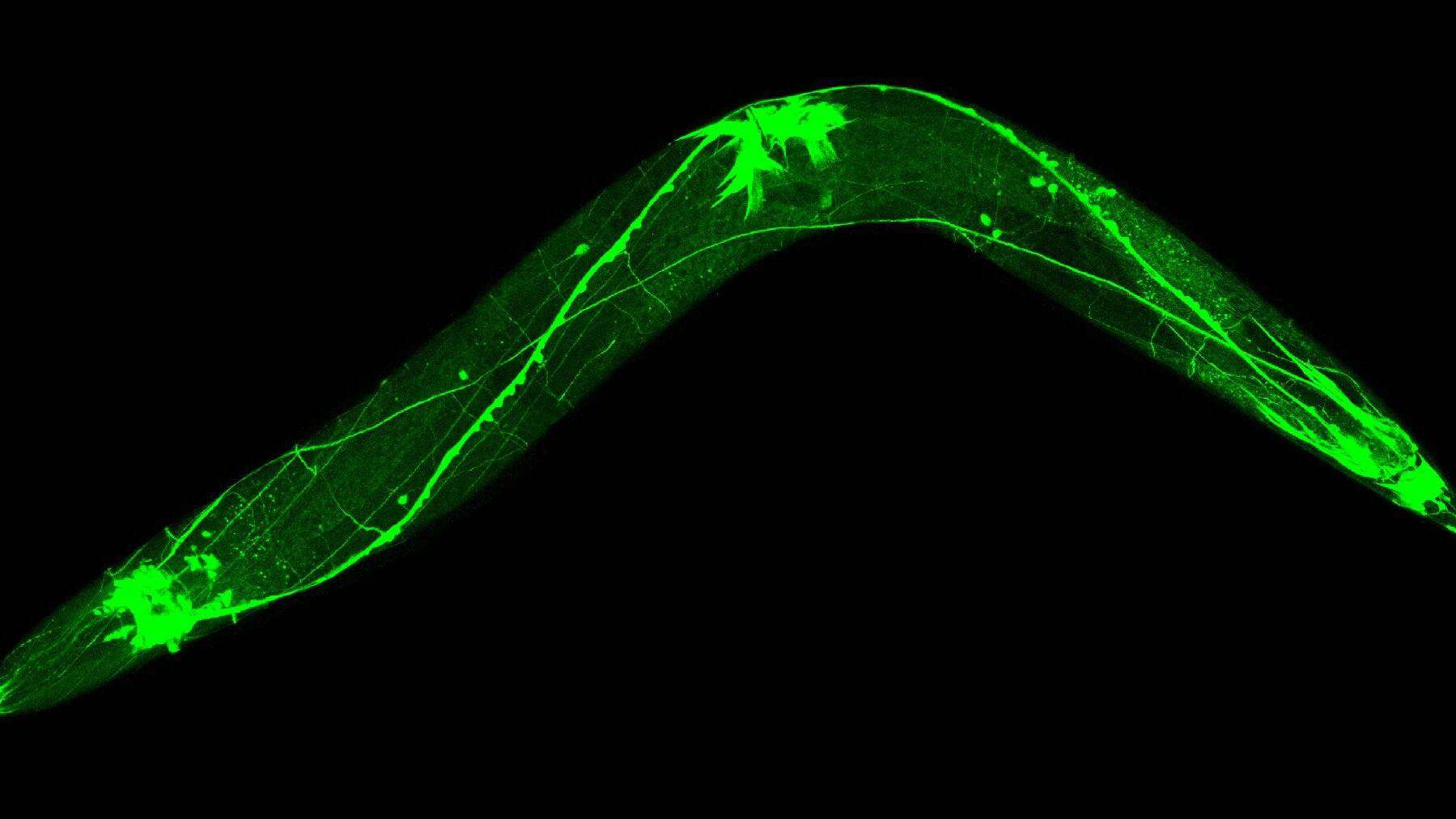

“The worm is very close to humans”

In this interview, Prof. Johan Auwerx from EPFL tells us how to eat if we want to live longer, what small worms can teach us about Alzheimer and Parkinson, and how the startup Nagi Bioscience removes bottlenecks in scientific research.

07.05.2019

“Things that work aren’t interesting“

Prof. Philippe Renaud from EPFL has been labeled a “serial startup producer” but says focusing on spin-offs is bad. In our interview, he gives us a glimpse of his independent thinking.

Startups,Innovation andVenture Capital

Sign up to receive our weekly newsletter and learn about investing in technologies that are changing the world.